Report on the Inquiry into Events Connected to Operation Gladio, 22 April 1992.

The open attempts made today to reduce Gladio to its initial phase and to justify that secretive organisation as an expression of patriotism and heroism cannot be allowed. There was no justification for Gladio, neither at its start nor by its end. Rather, its danger and illegitimacy increased as the years went by.

Reporting on Operation Gladio is challenging. The facts of Gladio are so troubling that they might be received by a reader as sensationalist at best, and paranoid at worst. For this reason, in this series of articles I have chosen to place at centre stage the translation of a document directly from the Italian Senate, with superscript annotations providing contextual information necessary to a foreign audience.

It is an early document (in that more evidence about Gladio has been uncovered since it was written) but I have chosen to translate and publish this 1992 report for the first time in English because it is a sober and level-headed narration of Gladio’s timeline which strikes a near perfect balance between conciseness and detail.

My additional commentary and analysis will be kept separate, with a final assessment in the last article of the series. Throughout, I will flag opinions that are my own, those of academics analysing events at a historical remove, as well as clearly state when contextual evidence strongly points to specific conclusions, but which remain unconfirmed. This is to not muddy the waters and give the impression I have taken poetic licence with what is a delicate chapter of European history.

This first article is an introduction to Gladio, establishing the historical context in which the Inquiry document was written and providing a short history of the turbulent Italian political events of the period. The beginning chapters of the report describing the birth of Gladio will be published over the coming weeks.

All translations are mine unless stated otherwise.

In 1988, the Italian Parliament created the Commissione Parlamentare d’Inchiesta sul Terrorismo in Italia e sulle Cause della Mancata Individuazione dei Responsabili delle Stragi, [Parliamentary Committee of Inquiry into Terrorism in Italy and the reasons for the lack of identification of perpetrators of massacres].

Since WWII, Italy had been rocked by a succession of subversive events: attempted military coups, acts of far right- and left-wing terrorism which collectively caused hundreds of deaths, and the assassination of Prime Minister Aldo Moro. There was a feeling that these cases had not been appropriately investigated and that many questions around them remained unresolved, so through Law 172 of May 17, 1988, a Committee was established to investigate:

a) The successes in the fight against terrorism and the current status of terrorism in Italy;

b) The reasons as to why the perpetrators of massacres and the facts relating to subversive actions in Italy have not been identified;

c) New information that can help to consolidate the the knowledge gained by the parliamentary inquiry into the via Fani massacre and the assassination of Aldo Moro;1The via Fani massacre occurred during the kidnapping of Aldo Moro, where five police officers in the ex-Prime Minister’s security detail were killed.

d) The activities connected to massacres or events aimed at subverting the Constitutional order, and the respective responsibility of apparata, structures or organisations and their past and present members.”

Originally scheduled to last 18 months, the parliamentary committee would instead conduct a 14-year inquiry that revealed acts of internal subversion and international collusion, eventually calling members of the highest political and military vertices to the stand. Over a million pages of testimonies, documents, and analysis were produced over the life of the investigation until its last sitting 2001, over a decade after it was initially planned to conclude.

It was over the course of these investigations that Operation Gladio was uncovered: on 24 October 1990, Italian Prime Minister Giulio Andreotti first revealed the existence of the organisation over the course of one of the Committee hearings. In a long testimony to the Chamber of Deputies, he stated:

It is an institution that exists within NATO framework and which, recalling the measures taken at the time of Nazi occupation, foresaw that there be a safeguard network on the territory in the case of occupation by foreign adversaries.2Parlamento Italiano, Camera dei Deputati, Resoconto stenografico: Seduta di mercoledì24 ottobre 1990, X Legisl., https://documenti.camera.it/_dati/leg10/lavori/stenografici/sed0537/sed0537.pdf, 63.

What he described are known as ‘stay-behind’ armies, where personnel is hidden in a country to organise resistance cells so that in case of an invasion, they can operate from behind enemy lines. This was what Gladio was conceived to be: a clandestine network of loosely-connected international intelligence and military organisations which operated covertly on European soil and could be mobilised in the case of aggression by the Warsaw Pact.

Despite Andreotti’s almost off-hand statements minimising the importance and reach of the organisation, the existence of these networks had enormous implications for European political and security structures.

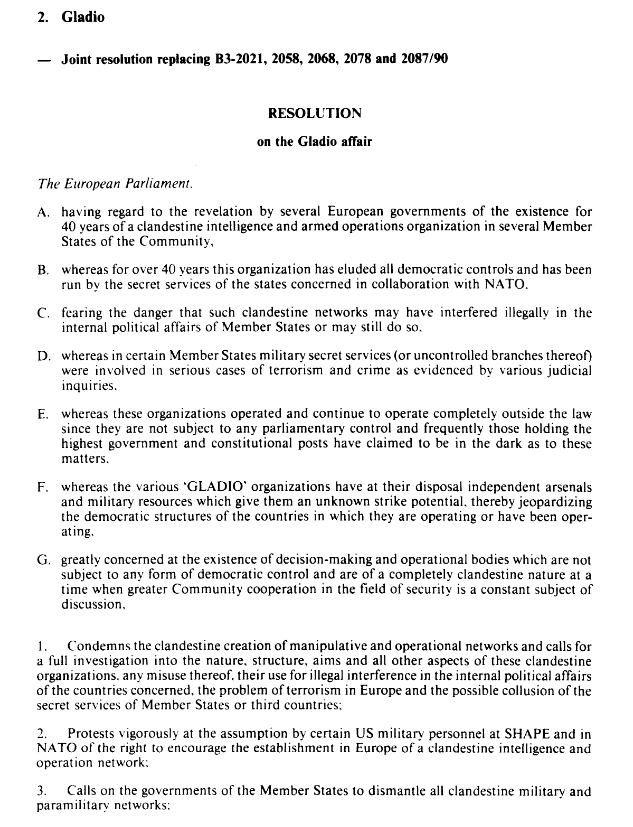

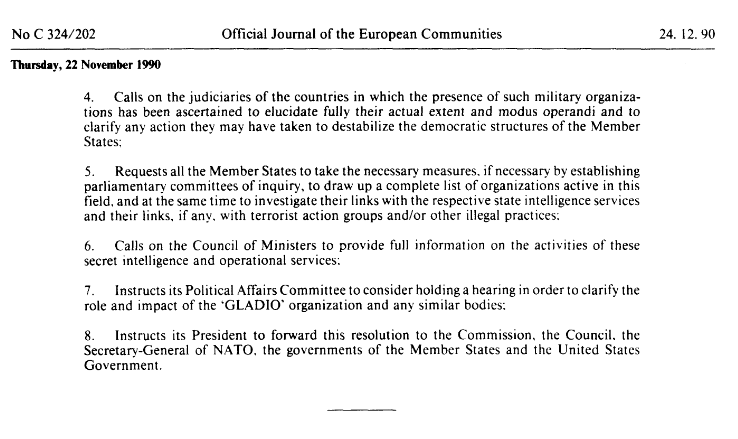

Shortly after his revelations, and after other European countries confirmed the existence of Gladio on their own soil, the European Parliament passed a resolution brimming with outrage. To understand how far-reaching the implications were to European democracy, the resolution deserves to be shown in full:

European Parliament, “Resolution on the Gladio Affair: Thursday, 22 November 1990”. Available here.

While Andreotti was the first to confirm the existence of the organisation, suspicions about the network had been in circulation for years. In 1984, troubling accusations against Italian security services had surfaced during a criminal trial but were initially dismissed as fantasy.

In 1972, three members of the Italian police, the Carabinieri, were murdered by a car bomb in Peteano, and for years this was blamed on the Lotta Continua [Continuous Struggle], a far-left paramilitary organisation.

Vincenzo Vinciguerra, a neofascist terrorist and member of ultra-right Ordine Nuovo [New Order], testified at his trial that he had been able to evade capture because the Italian security structures tacitly supported his anti-communist views, and aimed to discredit the Left by blaming terrorist attacks on far-left organisations:

With the massacre of Peteano and with all those that have followed, the knowledge should by now be clear that there existed a real live structure, occult and hidden, with the capacity of giving a strategic direction to the outrages. [This structure] lies within the state itself. There exists in Italy a secret force parallel to the armed forces, composed of civilians and military men, in an anti-Soviet capacity, that is, to organise a resistance on Italian soil against a Russian army.3Translation by Daniele Ganser, “Terrorism in Western Europe: An Approach to NATO’s Secret Stay-Behind Armies,” The Whitehead Journal of Diplomacy and International Relations, 2005, 71. Available at: document/f4e652a3-cad7-4284-9aae-243b630f3440/en/Terrorism_Western_Europe.pdf.

It would subsequently be revealed that Gladio had had remained active in Italy and Europe for four decades, operating outside the control of the state, its institutions, and the law. Its story has profound implications for how we understand Post-WWII history, the past and present European security structures, the role of diplomacy in international affairs, and the relationship between citizens and state.

What would otherwise have been a bombshell did not cause as much outrage or publicity that it may have deserved: Andreotti’s revelations came against the backdrop of a country beset by turmoil, as the late 1980s and early 1990s were years of seismic political shifts in Italy. We must go back a few years to understand the climate of the period.

Beginning in 1986, a bunker in the Ucciardone prison in Palermo hosted the largest trial in world history, where an attempt to dismantle the entire power structure of the Sicilian Mafia (Cosa Nostra) began with the indictment of 475 mafiosi. The trial lasted six years, until the Supreme Court upheld the conviction of 338 people after they had exhausted the appeals process.

This resulted in an all-out war against the state: the Mafia assassinated politicians, witnesses, judges, and magistrates – most famously Giovanni Falcone and Paolo Borsellino, whose heroic efforts leading the investigation made them targets of the organisation. They died within three months of each other in February and May of 1992.

This Maxi Trial revealed the inner workings and structure of the Sicilian mafia, but also began to uncover the extent of its political influence as mafiosi turned informants, the pentiti, provided credible information about connections to the highest levels of power. This avenue was not pursued at the time because of fears that investigations into the Cosa Nostra’s connections would face political roadblocks and jeopardise efforts to break up the organisation.

One of the most important witnesses in the trial and instrumental in uncovering the structure of the organisation was ex-mafioso Gaspare Mutolo. He refused to testify about the connection between the Mafia and the Italian political system:

[These] extremely complex and delicate situations (…) could – even in good faith – raise a dust that would risk seriously compromising the success of this investigation and what I believe to be the absolute priority: toppling the criminal Cosa Nostra organisation, whose danger is under everyone’s eyes, and is the foundation of all other problems.4La Vera Storia D’Italia: Interrogatori, Testimonianze, Riscontri, Analisi (Napoli: Tullio Pironti, 1995), 17.

It took another political scandal, Mani Pulite [‘Clean Hands’] to bring about a complete upheaval of the Italian political system and the death of the First Republic. This was a judicial investigation into political corruption, and at one point more than half of the Italian parliament was indicted, 400 city councils were dissolved, and prominent businessmen and politicians committed suicide after being publicly implicated in the scandal.

And within Mani Pulite, a massive political bribery system was uncovered – Tangentopoli [Bribesville or, to take the English custom, Bribesgate], where US$ 4 billion were paid annually in kickbacks by companies bidding for government contracts.5Stephen P. Koff, Italy: From the 1st to the 2nd Republic (London: Routledge, 2002), 2.

As a result of the revelations, all four parties in forming the 1992 government fell, including Democrazia Cristiana [Christian Democracy], which had ruled Italy for an almost uninterrupted 40 years after the defeat of Fascism and remained the largest force in Italian politics until the scandal. As a result of Tangentopoli it lost half of its votes in the 1992 elections, half again in 1993, withering away until its formal dissolution in 1994.

The post-war behemoth of Italian politics had fallen, the entire political system was recast through the birth of the Second Republic, and Gladio took second stage. However, the implications of the operation should be considered at least, if not more consequential than the Maxi Trial, Mani Pulite, and Tangentopoli.

But Gladio was not an exclusively Italian phenomenon. Nor should one reduce the operation to an expression of an institutionally weak and corrupt state, something that would not have occurred in other, more ‘stable’, more legally and structurally ‘civilised’ countries. The clandestine operation was present all over Europe and, if anything, the powers granted to the Commission and the degree of transparency and procedural rectitude shown by the Italian Parliament should be commended.

We only know about the extent of Gladio because of revelations made by Italy, as other European countries have been much less transparent about the operation. The only other effective investigation into the activities of Gladio occurred in Belgium.6See the official Parliamentary inquiry from the Belgian senate (in French and Dutch): https://www.senate.be/lexdocs/S0523/S05231297.pdf. The UK, one of the architects of the network, the USA, its main source of funding and coordination, and important centres like France and Germany have refused to give satisfactory information about Gladio to the public, which represents a gross breach of accountability to their citizens.

What sets the Italian case apart is the depth of inquiry that was conducted by the Commissione Stragi and the wealth of high-level testimonies available. However, this has also been a hindrance to its diffusion locally as well as internationally: isolating crucial and revelatory information has almost exclusively been the remit of historians, with even fewer reporters having the opportunity to approach the documentation and translate texts into English.

What will follow over the course of the next few weeks is a four-part translation of the history of Gladio which, to my knowledge, is the first time it will be available in English in full.

In certain Member States military secret services (or uncontrolled branches thereof) were involved in serious cases of terrorism and crime as evidenced by various judicial inquiries.

The various ‘GLADIO’ organizations have at their disposal independent arsenals and military resources which give them an unknown strike potential, thereby jeopardizing the democratic structures of the countries in which they are operating or have been operating.

European Parliament resolution on Gladio, 1990

Click here for the report describing the start of Operation Gladio in Italy.