By Ernest Harsch

Ernest Harsch holds a PhD in Sociology from the New School for Social Research in New York. He is currently a research scholar affiliated with Columbia University’s Institute of African Studies. Throughout a professional career as a journalist, he wrote mainly on international events, most extensively on Africa. His recent books are Thomas Sankara: An African Revolutionary, (Ohio University Press, 2014) and Burkina Faso: Power, Protest and Revolution (Zed Books, 2017), after earlier books on the struggle against apartheid in South Africa and the Angolan civil war. He worked on African issues for 25 years at the United Nations Secretariat in New York, including as managing editor of the UN’s quarterly journal Africa Renewal.

I originally commissioned this article for E-International Relations.

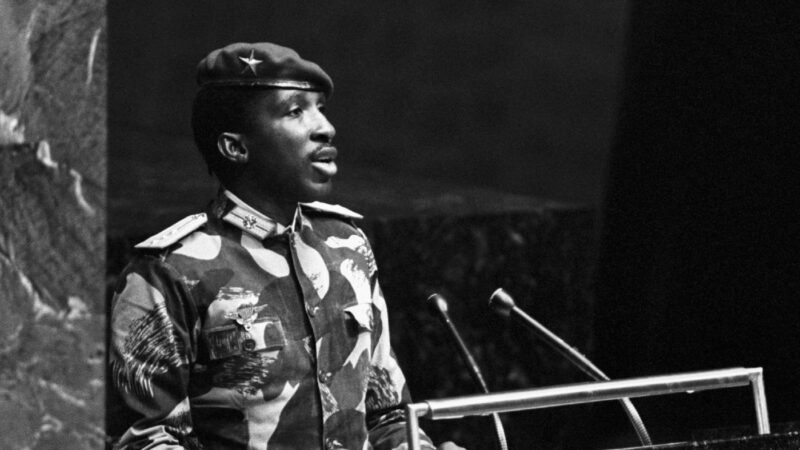

Long revered by radical youths and activists across Africa, Thomas Sankara finally also achieved a measure of government recognition in his country, Burkina Faso, on the thirty-sixth anniversary of his assassination in a military coup. For years, the commemorations of the late president’s death were organized by civil and political groups inspired by his revolutionary achievements and ideas. But on October 15, 2023, Burkina Faso’s governing military regime, keen for more popular support, made the anniversary an official event for the first time. Sankara was named a “hero of the nation,” the day was proclaimed an annual national holiday, President Ibrahim Traoré laid flowers at his memorial site, and one of the capital’s main thoroughfares was renamed for Sankara—from its previous designation as Boulevard Charles de Gaulle, the French president when the country gained its independence from France.

Burkinabè, as the citizens of that West African nation are known, have a keen sense of their history. For them, Sankara’s brief period at the helm, from 1983 to 1987, was a time when many changes came to their poor, landlocked country, and simultaneously transformed it from the little-know ex-colony called Upper Volta (Haute Volta in French) into the re-born Burkina Faso, “land of the upright” from two African languages. Many embraced the new name as unapologetically African and took pride in their charismatic young president, who audaciously challenged some of the most powerful countries on the world stage. While Burkinabè were most aware of his government’s domestic accomplishments, people elsewhere in Africa and beyond were attracted by Sankara’s frequent expressions of solidarity with oppressed people across the global South.

For a time, the replacement of Sankara’s government by a brutal authoritarian regime made it exceedingly difficult for Burkinabè to openly affirm his legacy. But pan-African networks of activists helped preserve and circulate his speeches and ideas outside Burkina Faso’s borders. As popular musicians in West Africa incorporated Sankara quotes and images into their videos, some inevitably reached a Burkinabè audience as well.

Researchers and scholars also helped disseminate the history of Burkina Faso’s “Sankarist” revolution. Collections of Sankara’s speeches and interviews were published in their original French and in English translation, as well as in various editions in Germany and South Africa, among other countries. A major website provided access to many original documents, analytical articles, news, commentaries, and reminiscences by Sankara’s colleagues. A number of books recounted the history of Sankara and his revolution, among them Bruno Jaffré’s pioneering biography in French. In English there have been this author’s two books (from which parts of this article are drawn), a short, popular biography of Sankara and a political history of Burkina Faso that devoted several chapters to the revolution. As well, a major recent historical work by Brian Peterson drew on new archival research and extensive interviews with Sankara’s contemporaries. And an edited collection provided numerous analyses and critiques of the Sankara era and its legacies.

An Unlikely Revolution

Before 1983, no one would have predicted that the country would have such a lasting a revolutionary experience. Decades of colonial rule by France had left the territory one of the poorest, least-urbanized, and least-developed in Africa. From the perspective of Paris, Upper Volta was a minor possession, with few exploitable resources beyond land to grow cotton or the labor of its people—hundreds of thousands of whom were conscripted to work on roads, railways, and plantations in other French colonies. Little was invested in infrastructure, economic development, or the health and education of the people. Independence in 1960 brought little change, except for political instability and a succession of coups.

To some observers, the August 1983 seizure of power by Sankara’s National Council of the Revolution (CNR) was just another military takeover. Certainly, Sankara was an army captain, and a number of key colleagues were officers as well. But they overthrew a previous military junta as part of a broad political coalition that included several leftist political groups, some trade unions, the student movement, and other civilian activists. The CNR and its cabinet were hybrid institutions that drew from various sectors of society and attracted strong and active support from the young, the poor, and others marginalized by the old order.

Like several other military-led revolutions in Africa (at different times, Benin, Congo-Brazzaville, Ethiopia, Egypt, Ghana, Libya, Madagascar, Somalia, and Sudan), the process initiated in 1983 could be considered a “revolution from above.” But it also had significant engagement from below.

The young leaders of the CNR (Sankara was just thirty-three at the time) made it clear from the outset that they were not interested in making just a few minor modifications at the top. They wanted to fundamentally transform the country, symbolizing that rupture by changing the country’s name from its old French colonial designation to one that asserted an unambiguous African identity.

Besides restructuring the judiciary, military, and other state institutions, the governing council attacked corruption and conspicuous consumption by the nation’s elite. Government ministers had their salaries and bonuses cut and their limousines taken away. Sankara publicly declared all his assets (and insisted his comrades do the same), kept his own children in public school, and rebuffed relatives who sought state jobs.

Sankara was open about his ideological beliefs: Marxist, but non-dogmatic. He refrained from calling the revolutionary process “socialist” or “communist,” often framing it instead as “anti-imperialist.” That entailed countering external domination, constructing a unified nation, building up the economy’s productive capacities, and addressing the population’s most pressing social problems, such as widespread hunger, disease, and illiteracy.

Particularly in such an arid country, environmental sustainability became a central priority. Hundreds of new wells were dug, and reservoirs built to better conserve the little water the country had. Farmers were taught how to combat soil erosion and improve their yields without chemical fertilizers. Millions of trees were planted across the countryside. In recognizing the importance of environmental issues, Burkina Faso was well ahead of many other African countries at the time.

It also was a forerunner in stressing improvements in women’s conditions and rights: women’s literacy classes, maternity training in rural villages, support for women’s cooperatives and market associations, and a new family code that set a minimum age for marriage, established divorce by mutual consent, recognized a widow’s right to inherit, and suppressed the bride price. Some women were appointed as judges, provincial high commissioners, directors of state enterprises, and even cabinet ministers.

‘A Troublesome Man’

On the external front, Burkina Faso’s policies and alignments took a sharp turn: away from France and other Western powers and toward anti-imperialist, revolutionary, and radical nationalist movements and governments across the global south. Few outside Africa had previously heard anything about the country, given its relatively small population (about 8 million at the time), miniscule economic weight, and location on the edge of the Sahara. But by speaking out at various international gatherings on behalf of many other countries and peoples, Sankara’s voice projected more strongly than some might have expected.

In part, that was because his messages echoed widely. But also because of the audacity with which he often presented them. A 1986 visit to Burkina Faso by French President François Mitterrand provided a dramatic illustration. Sankara departed from the host’s customary diplomatic niceties by challenging his visitor to a “duel” of ideas: a plea for the rights of the Palestinian people, defense of Nicaragua then under attack by US-backed “contras,” and criticism of the French authorities for their policies in Africa and toward African immigrants at home. Mitterrand set aside his prepared remarks and responded to Sankara point by point. He praised the Burkinabè president for his frank talk about such serious questions, and admitted that with Sankara, it was not easy to maintain a calm conscience or to “sleep peacefully.” Mitterrand quipped, “This is a somewhat troublesome man, President Sankara!”

Several overarching foreign policy goals emerged from Sankara’s speeches, declarations, and interventions at international meetings, including those of the United Nations, Non-Aligned Movement, Organization of African Unity (OAU, now the African Union), and other bodies. First, as exemplified by his interchanges with Mitterrand, he sought to establish as clearly as possible that Burkina Faso no longer followed direction from Paris, Washington, or other Western capitals (even though his government continued to welcome their financial aid). Second, Burkina Faso would assert its sovereignty by establishing relations with any state in the world, including those considered hostile to the West (Cuba, China, the Soviet Union, North Korea, etc.). Third, in accord with its revolutionary ideals, it would solidarize with—and sometimes directly assist—oppressed peoples and liberation movements across the globe. And fourth, it would press for genuine pan-African unity, to be expressed through concrete action by African governments and peoples, not just with occasional declarations.

In 1984 in Harlem, this writer first witnessed Sankara’s ability to connect with far-flung audiences. That year, the Burkinabè president set off to address the UN General Assembly. On the way he first stopped off in Havana, where he was awarded Cuba’s highest honor. Displeased, the conservative US government of President Ronald Reagan did not allow him to accept an invitation by Atlanta’s mayor, a prominent African-American civil rights figure, to visit that city on his way to the UN. Limited to New York City, Sankara instead addressed a public meeting at a high school in Harlem, where he spoke to a largely African-American crowd of some 500. In an animated talk that included call-and-response exchanges with the cheering audience, Sankara praised Harlem as a center of Black culture and pride and asserted that for African revolutionaries, “our White House is in Black Harlem.”

The next day Sankara spoke at the UN General Assembly. Among a range of other international topics, he touched on a number of US policies, including US support for Israel against Palestinian rights and its own military invasion of the Caribbean island of Grenada the year before. He affirmed solidarity with Nicaragua’s Sandinista revolutionaries, who were then fighting against US-backed rebels. The next year, Sankara visited Nicaragua itself (following another stop in Cuba). There he spoke to a crowd of 200,000 on behalf of all foreign delegations attending a celebration of the Sandinistas’ twenty-fifth anniversary. It was not surprising, therefore, that the government of a small Sahelian country would arouse notable enmity from Washington, as Sankara biographer Peterson confirmed when he uncovered previously classified US diplomatic cables.

Although a strong advocate of pan-Africanism, at the time Sankara had only a few allies among other African heads of state, some of whom he severely criticized for not doing more to build African unity or lessen the suffering of their people. At annual summit meetings of the OAU and during his frequent trips in Africa, he urged Africans to give much more support to the continent’s liberation movements, specifically the struggles in South Africa and Namibia against the white minority apartheid regime. One of his final acts, just a few days before the coup that would end his life, was to host a pan-African anti-apartheid conference in Ouagadougou, the Burkinabè capital. Participants focused on practical ways to assist Southern Africa’s liberation fighters and castigated African governments that collaborated with the apartheid authorities.

Seeing that Africa’s development prospects were being crippled by its crushing foreign debt to Western creditors, Sankara, at a July 1987 summit of the OAU, urged African leaders to simply refuse to pay. Acknowledging that individual African countries were too weak to do so on their own, he proposed that African countries create a “united front” against the debt. The OAU never followed Sankara’s advice.

While a number of African leaders were annoyed or irritated by Sankara’s chidings and criticisms, a handful were more openly hostile. In December 1985, the better-armed government of neighboring Mali provoked a brief border war with Burkina Faso, which some analysts saw as partly motivated by fear that Sankara’s popularity among some sectors within Mali could contribute to domestic opposition to that regime. The dictatorship in Togo, another neighboring state, actively supported dissident Burkinabè exiles hostile to Sankara.

Relations with the government of neighboring Côte d’Ivoire were especially tense. Historically, large numbers of Burkinabè migrants lived and worked there, causing the authorities some anxiety over possible loyalties to Sankara and his fellow revolutionaries. The Ivorian government was one of France’s closest allies in Africa and its conservative president, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, was leery of the Burkinabè government’s anti-imperialist stance. He also was well-positioned to influence Burkina Faso’s political course: in 1985 an adopted daughter of Houphouët-Boigny managed to marry the second-highest Burkinabè leader, the minister of defense, Captain Blaise Compaoré.

On October 15, 1987, Compaoré led a coup against Sankara, assassinating him and a dozen aides that day (and more subsequently). A variety of factors played into the coup: infighting among the various political factions within the National Council of the Revolution, alarm that Sankara’s strenuous anticorruption measures might expose or hinder those engaged in illegal dealings, and pressures from abroad, including France and Côte d’Ivoire, to tone down the country’s anti-Western stance. Many Burkinabè believed that France, either directly or through their ally Houphouët-Boigny, helped instigate the coup.

Although Compaoré initially claimed to be “rectifying” the revolution, his takeover led to its outright collapse. Burkinabè were shocked and terrified. The Compaoré regime eventually scuttled most of the progressive policies and programs of the Sankara era. Externally, relations grew close with the governments of Côte d’Ivoire, Togo, France, and other Western powers. The French authorities regularly welcomed Compaoré to Paris.

Thanks to significant financial aid from France and other powers and a readiness to use the most brutal force against domestic opponents, Compaoré was able to build a formidable machine capable of lasting twenty-seven years. Under French urging, Compaoré embellished his authoritarian regime with a veneer of multi-party democracy. Despite regular elections, he retained his political dominance through a mixture of electoral fraud, repeated constitutional manipulations, and the corruptions of an extensive patronage system.

The Return of ‘Sankarism’

What Compaoré did not expect was that Sankara’s name and legacy would resurface—and loom large as popular discontent mounted. Despite the regime’s repression and success in suppressing formal opposition in the electoral arena, protest and rebellion began to erupt more frequently from the late 1990s onward.

As I previously wrote, those challenges opened the way for more overt expressions of admiration for Sankara during the following decade. It was marked most visibly by periodic commemorations of the anniversary of Sankara’s assassination, as well as by the emergence of a variety of small political parties, student associations, and other groups that explicitly drew inspiration from the ideas, practices, and achievements of the revolutionary era.

Not all were drawn to Sankara’s example for the same reasons. Some admired his anti-imperialism and dedication to building national sovereignty. Others appreciated his practical ideas for economic and social development. Many cited his personal integrity and efforts to eradicate corruption. Some acknowledged that there had been human rights abuses during his presidency, but tended to blame those on hardliners and zealots within the CNR—some of whom were aligned with Compaoré.

Meanwhile, the foundations of the Compaoré regime started to erode. After repeated manipulations of the constitution to enable him to stand for reelection beyond the constitution’s original term limits, he sought to do so once again in 2013. But that was a step too far. Already incensed by widespread poverty, rights abuses, and rampant corruption, people across the country reacted in anger and outrage, crystallized in their demand that Compaoré leave power after the end of his current term. When he pushed ahead anyway, unprecedented mass rallies, marches, and general strikes swept the country, the popular pressure impelling the fragmented opposition parties, activist groups, and trade unions to mount a coordinated struggle.

Most of those groups’ leaders did not particularly draw inspiration from Sankara. They simply wanted Compaoré out, to be replaced by a more genuine democratic system. Yet in the months leading up to Compaoré’s ouster, symbols of Sankara were virtually everywhere. Protesters carried his portrait. His recorded voice rang out over sound systems. Quotations from his speeches were featured in popular chants. Even politically moderate opposition leaders often concluded speeches with the emblematic slogan of Sankara’s revolutionary government: “La patrie ou la mort, nous vaincrons!” (Homeland or death, we will win!).

One of the main activist groups was Balai citoyen (“Citizens’ Broom”), launched just a couple of years earlier by several musicians with wide followings among Burkinabè youths. According to one of them, the rap artist known as Smockey, they adopted Sankara as their symbolic patron. Smockey later told me that they admired Sankara’s “courage and determination to build a Burkina Faso of social justice and inclusive development,” as well as his personal “simplicity, modesty, and integrity … a model for anyone aspiring to manage public property.”

During the final week of October 2014, with Compaoré stubbornly refusing to abandon his efforts to violate the constitution, the demonstrations acquired an insurrectionary momentum. As several dozen protesters fell before the bullets of the security forces, the activists of Balai citoyen and other youth groups erected barricades, occupied the streets, and seized key government installations. Compaoré fled the country, under the protection of French special forces.

Two weeks later, a transitional government was formed, with a mandate to conduct essential reforms and prepare new elections. The cabinet and interim parliament were politically diverse, including technocrats, intellectuals, army officers, civil society figures, and a few radical activists, among them several Sankarists. Following a failed attempt to retake power by a pro-Compaoré military faction, elections were ultimately held in November 2015. The winners had once been leading figures in Compaoré’s party, although they had broken with him before the final political showdown. Admirers of Sankara were influential in the realm of ideas, but much less in terms of practical politics, in part because they were fractured into numerous parties and associations.

Meanwhile, judicial prosecutors opened an inquiry into Sankara’s assassination, as well as several other political murders during the Compaoré era. They conducted forensic analyses, took testimony from witnesses, and were able to acquire some previously secret documentation from France. More than a dozen individuals were ultimately charged, including Compaoré, who was then living in exile in Côte d’Ivoire and could therefore be tried only in absentia. The trial began in October 2021 and lasted six months. Several were acquitted or received suspended sentences. The military tribunal sentenced others to varying prison terms—and Compaoré and two others to life.

The court maintained an international arrest warrant against Compaoré (although the Ivorian government refused to respond and even afforded him citizenship). Activists also urged investigators to continue gathering evidence on the international aspects of the case, including the roles of Côte d’Ivoire, France, and any other government that might have been involved. Although the French authorities previously declassified some documents, they did not release any under a “national defense” designation, stoking suspicions that they had something to hide.

In the meantime, the elected government of President Marc Roch Christian Kaboré struggled with an Islamist insurgency initiated by groups affiliated with Al-Qaida and the Islamic State. Initially the insurgents struck into Burkina Faso from bases in neighboring Mali and Niger, but gradually took root within the country. By 2022 large parts of the border regions of the north and east had escaped effective government control, and the tolls of Burkinabè civilians killed or displaced from their homes mounted.

The Kaboré government’s inability to ensure security triggered a military coup in January 2022, and when that junta foundered on the battlefield, another one in September. The new leadership, headed by Captain Ibrahim Traoré, took a more energetic approach, including through popular mobilizations. Both to strengthen that effort and to shore up their own political legitimacy, the authorities repeatedly invoked Sankara’s legacy.

Activists who had long advocated the ideals of Sankara’s revolutionary era welcomed that official support. But perhaps realizing that government backing might eventually fade or end, they also emphasized the need to maintain a grassroots momentum. Speaking on the anniversary of the late president’s assassination, Daouda Traoré, vice-president of the committee that initiated the Sankara memorial in Ouagadougou, vowed that he and his colleagues would not only expand the site, but also their educational activities. He said that promoting Sankara’s “memory and values”—and linking his vision to concrete actions—was important for the people of Burkina Faso and the rest of Africa.